How Roland Engineered the 80s

The Technical History of the TR-808

In the early 1960s, electronic organs were showing up in Japanese homes, schools, and churches. Most were played without a rhythm section, in places where having someone else play along just wasn’t part of the setup.

At the same time, electronic systems were becoming comfortable with counting and switching. Transistorized clocks and calculators were already dividing time into stable units, and organs themselves relied on fixed oscillators and logic to generate pitch. Electronics were not yet capable of shaping expressive sound, but they were reliable at keeping time.

Rhythm sat at the intersection of those two realities. It was musical, but it could be broken down. It could be counted, divided, and triggered using technologies that already existed. For engineers working with transistors and discrete logic, rhythm presented itself as an open experiment.

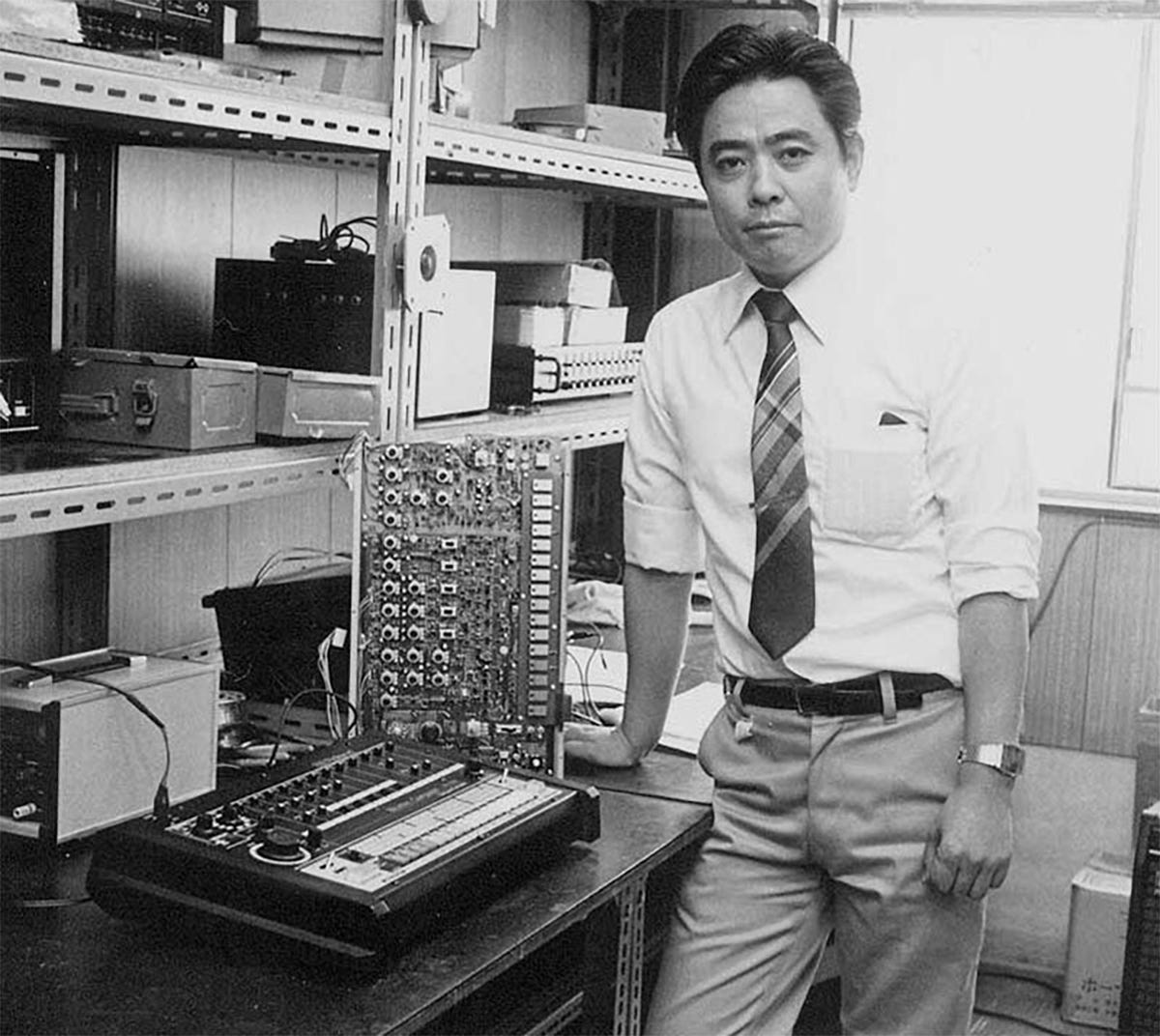

In 1964, Ikutaro Kakehashi gave that experiment a physical form with the Ace Tone R-1 Rhythm Ace. One of the earliest fully transistorized rhythm devices produced domestically, it offered no programmability and stored no patterns. That wasn’t the point. It demonstrated that rhythm could be generated electronically by circuits reliable enough for everyday use, allowing a machine to take on a role that had previously required another person.

That concept was extended in 1967 with the Ace Tone FR-1 Rhythm Ace. Preset rhythms could now be selected and combined using fixed hardware logic, allowing users to move between patterns without altering the circuit itself. The machine no longer produced a single behavior, but a controlled range of them. Identical units could be manufactured and distributed without drifting out of spec, turning rhythm into something that could be installed rather than performed.

When Roland Corporation was established in Osaka in 1972, Kakehashi reorganized this work for scale and export rather than continued experimentation. The company was structured to design, manufacture, and distribute instruments as a single system, with international markets considered from the outset. Early Roland rhythm machines such as the TR-33, TR-55, and TR-77 carried forward the rigid logic of the Ace Tone designs, expanding how patterns were selected and synchronized while remaining fundamentally hardware-defined. These were production tools built for durability, repetition, and unattended operation.

At the same time, synthesizers remained expensive, fragile, and largely confined to studios or academic settings. Roland approached electronic sound from a different direction, designing instruments meant to live alongside organs and ensemble keyboards rather than replace them. Early Roland synthesizers emphasized selection over construction, with fixed modulation paths and standardized voltage control ensuring predictable behavior whenever the instrument was powered on. Electronic sound became usable without requiring technical mediation.

Roland applied a similar mindset to dynamics with the EP-30 electronic piano. Earlier electronic keyboards had proven practical, but they remained dynamically flat and disconnected from touch. The EP-30 translated key pressure directly into control signals, allowing articulation and volume to respond to the player without mechanical complexity. The instrument mattered because it proved that expression itself could be captured, processed, and stabilized within an electronic system.

By the early 1970s, microprocessors had already entered everyday Japanese products, particularly calculators and electronic timekeeping devices. These systems taught processors how to count, store values, and execute instructions without drift. When processors became reliable enough to leave clocks and calculators, their most immediate role in music was control rather than sound generation.

Roland gave that role a dedicated machine in the MC-8 Microcomposer. The MC-8 produced no sound of its own. Musical information was entered numerically, as sequences of values representing pitch, duration, and timing, then sent as control signals to external synthesizers and rhythm machines. Music became math, and once entered, timing no longer depended on sustained human attention. The MC-8 defined structure with a patience and precision that performance could not maintain indefinitely.

That logic soon moved directly into rhythm machines. With the CR-68 and CR-78, microprocessors were embedded inside the instrument, allowing patterns to be written, stored, and recalled rather than selected from fixed presets. Memory became part of the machine itself, ensuring rhythm persisted beyond the moment of performance or power.

By 1980, Roland had already proven stable analog sound generation, microprocessor control, and onboard memory as separate ideas. The TR-808 was the point where these elements converged inside a single, affordable system. It was marketed as a programmable replacement for earlier preset rhythm boxes, with no claim to revolution. Its ambition was modest, even conservative, in how it presented itself.

The sound of the TR-808 took shape under constraint. Engineer Tadao Kikumoto was working within strict cost limits at a moment when semiconductor manufacturing was rapidly tightening tolerances. The transistors used in the machine functioned correctly, but failed to meet the noise and leakage specifications required for high-fidelity audio equipment. Mitsubishi had rejected them for conventional use because they were too noisy for amplifiers and broadcast electronics. Roland acquired them deliberately.

That excess noise became material. When amplified and filtered, it produced the unstable hiss of the hi-hats, the grain of the snare, and the brittle texture that defined the machine’s upper register. These characteristics were not corrected or smoothed away. They were stabilized and held inside a circuit that enforced timing. Imperfection was bounded and made usable.

When semiconductor manufacturing improved and those noisy components disappeared from production, the sound disappeared with them. Rather than redesign the circuit to imitate what had been lost, Roland ended production of the TR-808.

What followed did not originate inside studios. It took shape wherever the machine was evaluated on its own terms rather than against acoustic drums. The sustained bass drum became a low-frequency voice, repetition shifted from accompaniment to structure, and patterns moved from background to foundation. The machine itself remained unchanged as interpretation evolved around it.

That shift was audible rather than theoretical. An 808 kick is not a complex sound but a decaying sine wave, closer to a test tone than a drum. Its simplicity allowed it to pass cleanly through radio transmission, cassette duplication, and broadcast compression, leaving little to be degraded. The machine was broadcast-ready by nature.

As music production moved away from performance and toward assembly, the TR-808 fit naturally into that transition. One person could define tempo, structure, and weight alone, without shared space or sustained coordination. By the middle of the 1980s, its rhythmic DNA was audible across global popular music.

The TR-808 emerged from a way of thinking that treated rhythm as an engineering problem rather than a musical one, shifting responsibility from the performer to the system. And that may be the most lasting thing Roland ever engineered.

Nice to see an article on Roland. Always was a big fan of them, especially for MIDI devices.

Good stuff man. The 808's contributions to music cannot be overstated.