When Sega Built the Most Extreme Arcade Cabinet

The R360 story

Before the R360 existed, Sega had already stretched the definition of what an arcade cabinet could be. Sega never treated the cabinet as a passive shell for software. For Sega, the cabinet itself was part of the experience. The screen, the enclosure, the posture, and the movement mattered as much as the game board inside it.

This approach developed gradually. Through the early and mid-1980s, Sega pushed cabinets away from static boxes and toward machines that acted directly on the player’s body. Each iteration removed an abstraction and exposed another. As graphics improved, Sega learned that visual fidelity alone produced diminishing returns.

By the end of the decade, Sega’s arcades had become a proving ground for mechanical ideas that would not survive ordinary product planning. Internally, these machines were treated less like retail products and more like sanctioned experiments, where weight, cost, and maintenance were tolerated if the result drew attention. This tolerance built incremental confidence.

By the early 1990s, that excess had backed Sega into a corner. Nearly every conventional method of achieving immersion had already been exhausted.

The next step did not come from inside the company.

In Perth, Australia, an unauthorized machine running Sega’s After Burner rotated players across three axes. When word reached Sega headquarters, Managing Director Hisashi Suzuki sent Masaki Matsuno to inspect it in person.

Matsuno found a crude machine that resembled an aircraft trainer more than an arcade cabinet. Its construction was rough and its movement imprecise, but it pointed to a form of control Sega had not yet considered.

When Matsuno returned to Japan, Suzuki asked a practical question. Could Sega build its own version?

A small team formed under Matsuno, made up largely of young engineers in their early twenties, recruited more for mechanical hobbies than arcade design. Senior staff were skeptical. The project carried obvious cost and safety risks.

Rather than starting with specifications, the project began with engineers strapping themselves into improvised machines. On the roof of a Sega building, the team mounted a seat inside a modified cable drum and rolled it by hand, observing how disorientation and nausea set in. These reactions were recorded, not discouraged.

Prototypes followed. The wooden drum gave way to steel pipe frames. Rotation along individual axes was introduced manually, then by motors. Safety belts were added and repositioned. The goal was to learn how much movement a player could endure without breaking the experience.

The defining solution was a full circular arc surrounding the cockpit and carrying the entire load. The cockpit rode the arc; an external motor drove the pitch while an internal one handled the roll. Continuous rotation depended on the arc remaining nearly perfectly circular.

That requirement immediately created manufacturing problems. Bending the steel arc introduced internal stress, and early versions developed fine cracks under repeated motion. Only after multiple revisions did the problem stabilize, at significant cost.

Assembly was equally difficult. The arc was built in sections, and the cockpit was lowered into place by crane before the frame was closed around it. At the Yaguchi plant in Chiba Prefecture, production resembled rail or aircraft assembly more than arcade manufacturing. Even under ideal conditions, Sega could complete only three units per day.

Electrical design exposed the project’s central challenge. The cockpit rotated continuously while power, video, and control systems remained stationary. All signals had to pass through a moving interface. Wireless transmission was not viable. The solution was industrial slip rings.

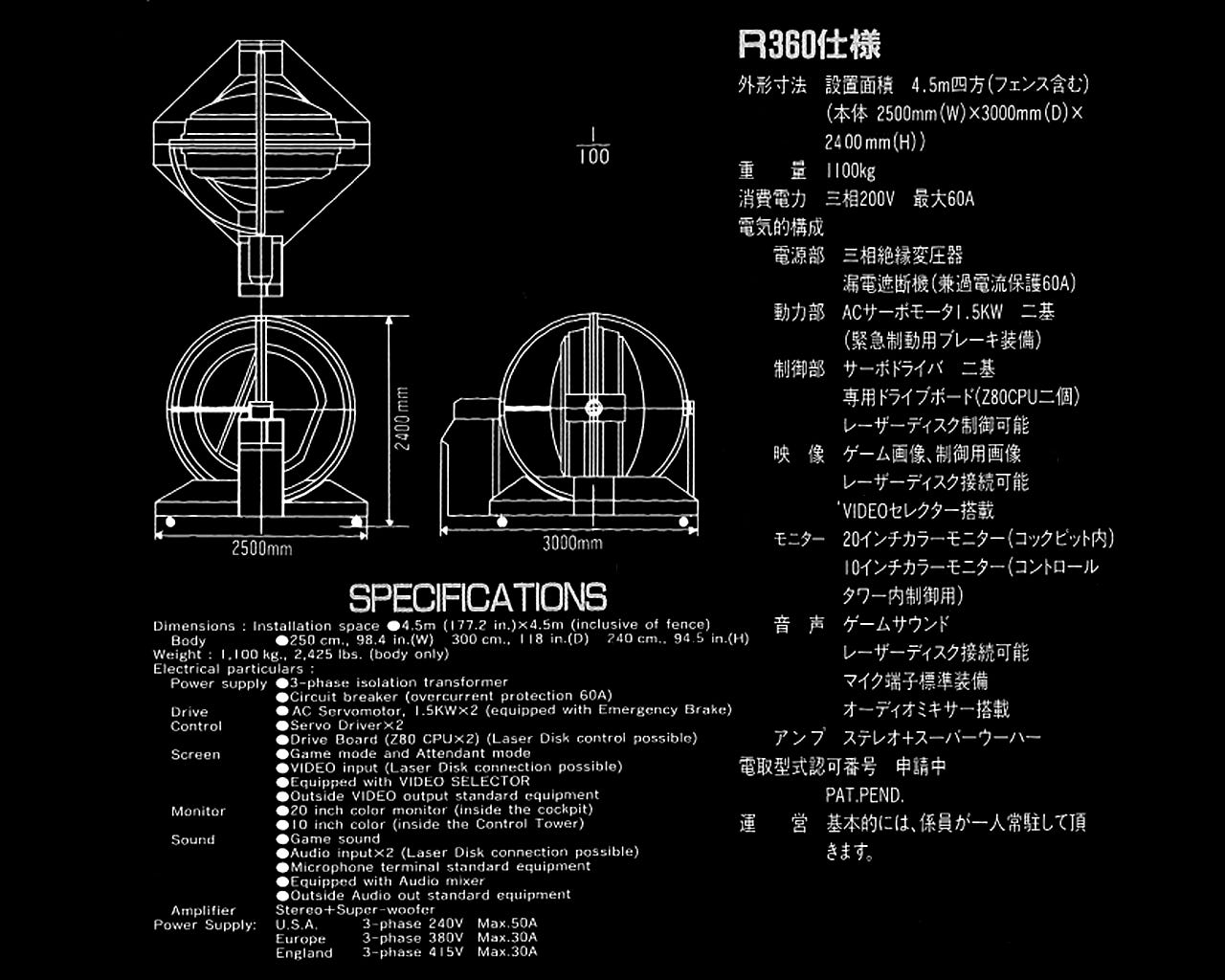

Yoshimoto selected platinum-contact slip rings used in military radar equipment. Two were required; though functional, they wore over time and demanded specialized replacement. Each unit cost roughly one million yen. Sega had effectively built a toy that required military-grade maintenance. The drive system relied on Toshiba 1.5-kilowatt AC servo motors. The cabinet demanded industrial 200-volt three-phase power, forcing operators to rewire entire venues for a single machine.

Even the display introduced problems. CRT monitors relied on magnetic fields to steer the electron beam across the screen. As the cabinet rotated, those fields shifted, warping the image. The solution was continuous degaussing during operation; it reduced distortion but never eliminated it. The limitation was accepted, not solved.

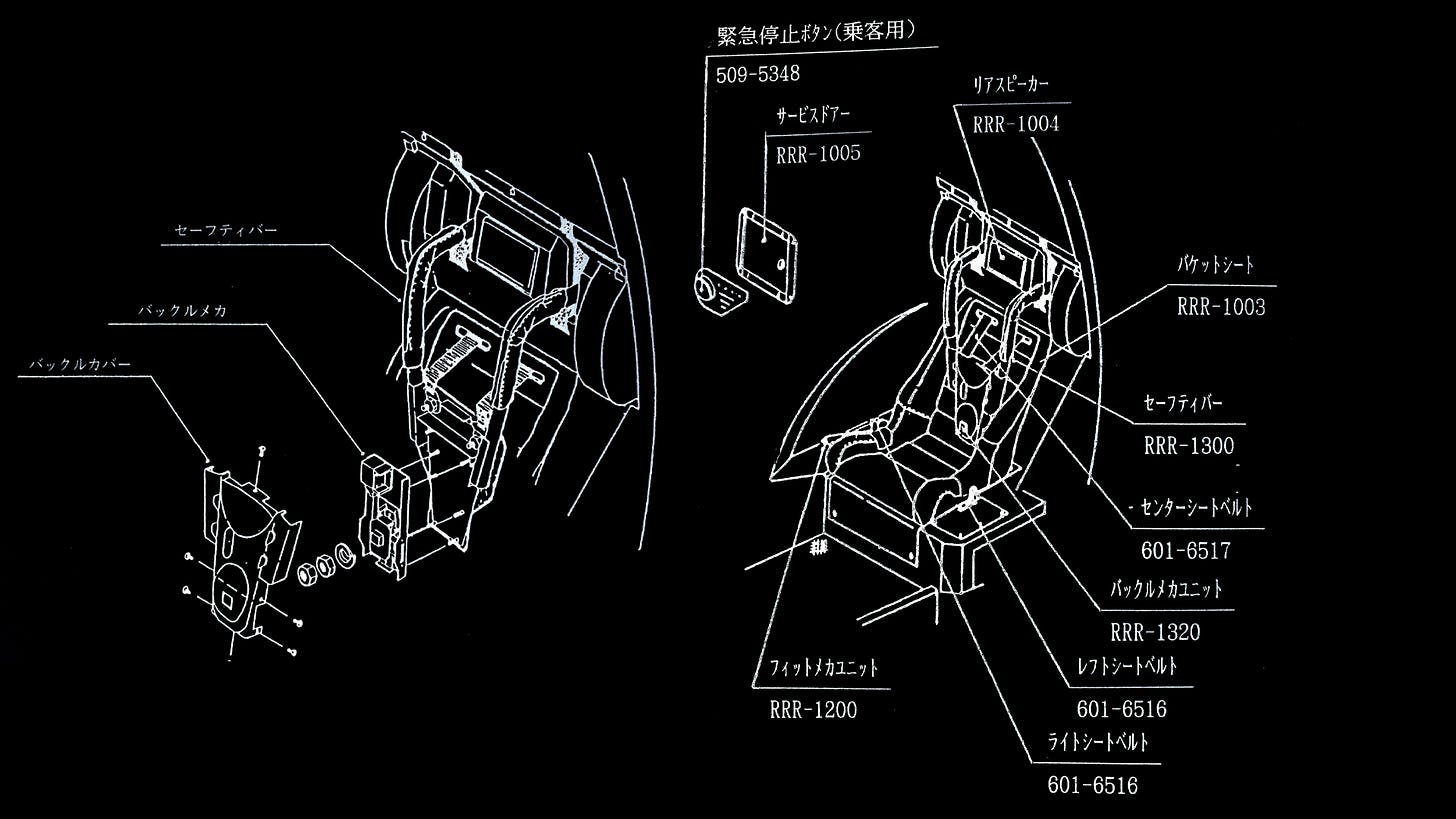

Safety dominated the final design, but in a narrow sense. The restraint system alone took over a year to finalize. Riders were enclosed in a molded fiber-reinforced plastic seat, secured by a steel safety bar and multiple belts tightened externally. Once operation began, riders could not release themselves.

This approach solved one problem and exposed another. During development, a tester was left suspended upside down for several hours after an emergency stop and was discovered by chance. The system prevented ejection, but provided no reliable means of recovery. The design remained unchanged. Human intervention became a permanent requirement.

Motion was limited to under 2 G. Emergency stops were installed on the cockpit and externally. A staffed control tower housed the main board and monitoring displays, and the system would not operate without an attendant key. Fencing, pressure mats, and proximity sensors enclosed the installation.

When completed, the R360 was prohibitively expensive. The list price was ¥18 million, with most units selling closer to ¥16 million, approximately $100,000 in 1990 dollars. Production was capped at 150 units.

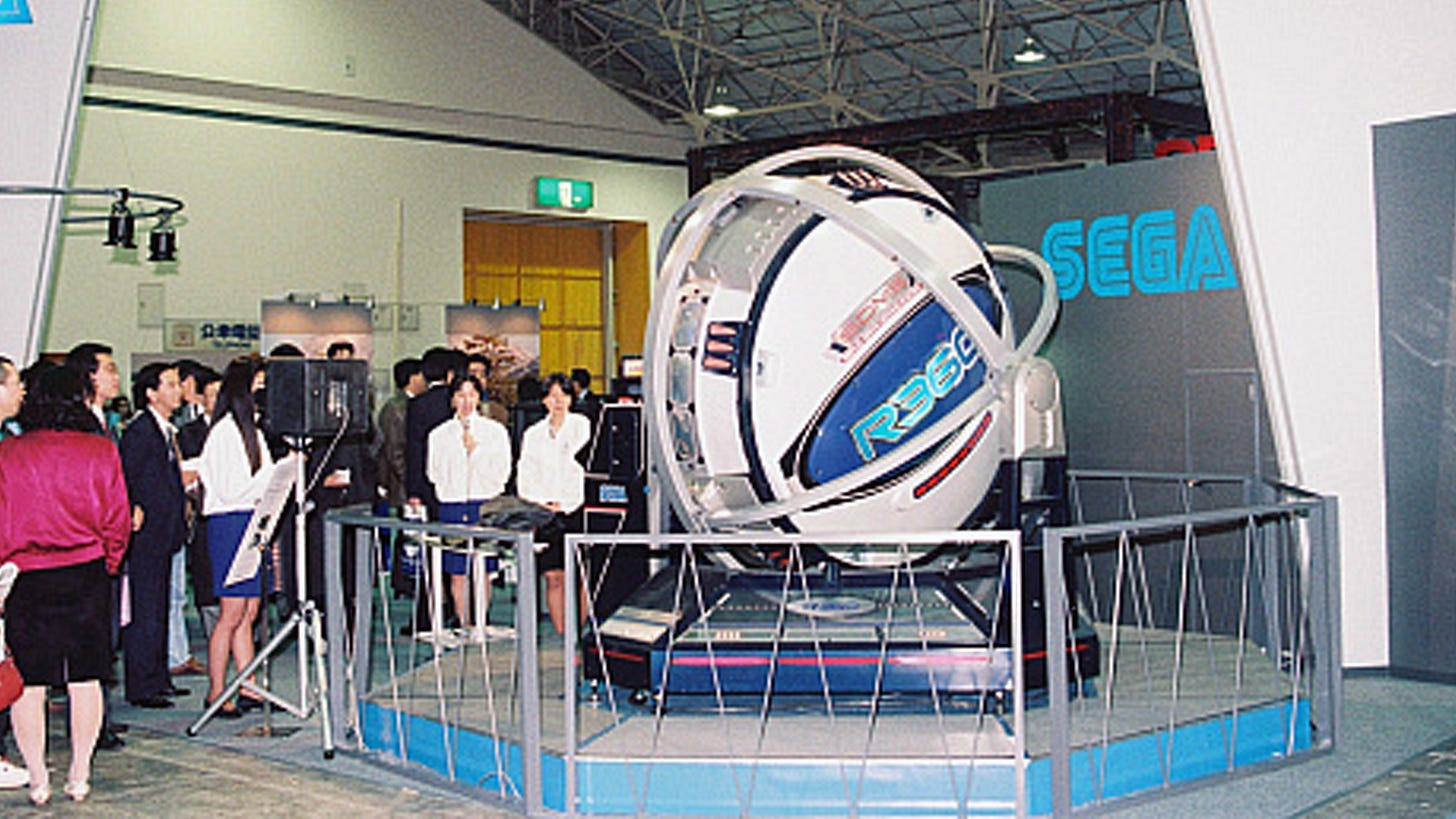

The R360 debuted publicly on July 3, 1990, at the Haneda Tokyu Hotel. The cabinet weighed roughly 1.5 tons. It was delivered the same day. Cranes were required. Engineers worried about floor loading and power capacity. Plywood covered the carpet. The demonstration proceeded. The first installed game was G-LOC: Air Battle, a jet combat game built around high-speed turns and sustained aerial maneuvers.

Location testing followed at Hi-Tech Land Sega Shibuya. The R360 cost 500 yen per play, compared to the standard 100 yen for regular cabinets. Use rarely exceeded 100 plays per day, while the machine consumed disproportionate floor space, staff time, power, and attention. Suzuki reportedly referred to it as a “panda,” a rare attraction whose value lay not in revenue, but in spectacle. In practice, it functioned as a luxury billboard for the brand.

After its brief commercial life, units were exported and gradually withdrawn. One operated at Disneyland. Another was reportedly owned by Michael Jackson at Neverland and vanished after his death. A Canadian unit was damaged during electrical work and scrapped.

For years, Sega could not confirm the existence of a single functioning machine. Eventually, one resurfaced in private hands. Sega does not appear to have kept one.

The R360 existed within a narrow window. A few years earlier, the technology would have been technically unfeasible. A few years later, the economics of arcades would have made it indefensible. It appeared when excess was still tolerated and sustainability had not yet become mandatory. What it demonstrated was not a future, but a boundary. It showed how far mechanical immersion could be pushed before collapsing under its own weight.

Pops up in Terminator 2, in the arcade scene. Edward Furlong is playing in it when his buddy tells him the cops are looking for him